WOOL: Chapter 1

A lamb named Penny, civilization's first mouflon, and the story of the Golden Fleece. In part one of this series, we begin with sheep—how they live, where they come from, and what they represent.

So, you’ve come for the 12-part series about wool. I want you to know that your enthusiasm energized me to return again and again to make this first chapter as good as it could be. To begin, I think it makes the most sense to start at the source: with sheep. Of course there are other animals that produce wool. Alpacas, yaks, even rabbits. We’ll talk about those animals in a later chapter, but because sheep wool is the most widely used animal fiber1, we’re focusing first on them.

In this chapter, I’ll take you through the birth of a lamb named Penny and her life in Oregon. Will she get sent to the market or will she be kept to produce gorgeous wool? Then we’ll journey back to 11,000 BC when humans first realized they could coral mouflon (aka wild sheep) and use them for meat, work, milk, and wool. Here, I’ll tell you a little more about the origins of the celebrity status Merino breed. Finally, we’ll close out the chapter with the layered symbolism of lambs, sheep, and rams—such as Mary Had a Little Lamb and the Lamb of God. In the chapters after this one, we’ll follow wool beyond the pasture and into the world of textiles, tracing the processes that turn raw fiber into finished fabric.

If you like wearing wool and want to know more about this exceptional fiber, I’m writing this series for you. Consider me your personal researcher into the world of wool. I’ve included footnotes for those who want to click around more and/or double check my reporting. Putting this together took many delightful, diligent hours of research, and I have even more to share with you soon. You can expect me to go just as deep in every chapter that follows, publishing monthly.

Shall we begin?

Life of a sheep

Late afternoon on March 13, 2025, it’s cold and damp on a farm in Eugene, Oregon. In a dimly-lit blue barn, a ewe paws the ground, arches her back, and strains to push out a little lamb named Penny. She is slick with amniotic fluid and the loving mama vigorously licks her lamb clean, and after the lamb finds her footing in the soft straw, she latches onto a teat to drink milk for the very first time. Within a half hour, the ewe is in labor again, with Penny’s brother, Pierre.

The shepherdess of this farm, Stéphanie Schiffgens, stays close, barely intervening except to rub an antiseptic on the umbilical cords and flick on a heat lamp that will keep these three warm and cozy. For the next few days, the newborns and their mom will get to know one another in this precious, safe space. Once the lambs become less wobbly and a little bit sturdier on their legs, and it’s clear they’ve imprinted on mama, they’ll return to the rest of the flock.

“Ultimately, that’s what their life is going to be like,” Schiffgens says. “Even after the mom has her lambs, they still cherish being with the rest of the herd.”

Then the nursery stall becomes available for the next round of births.

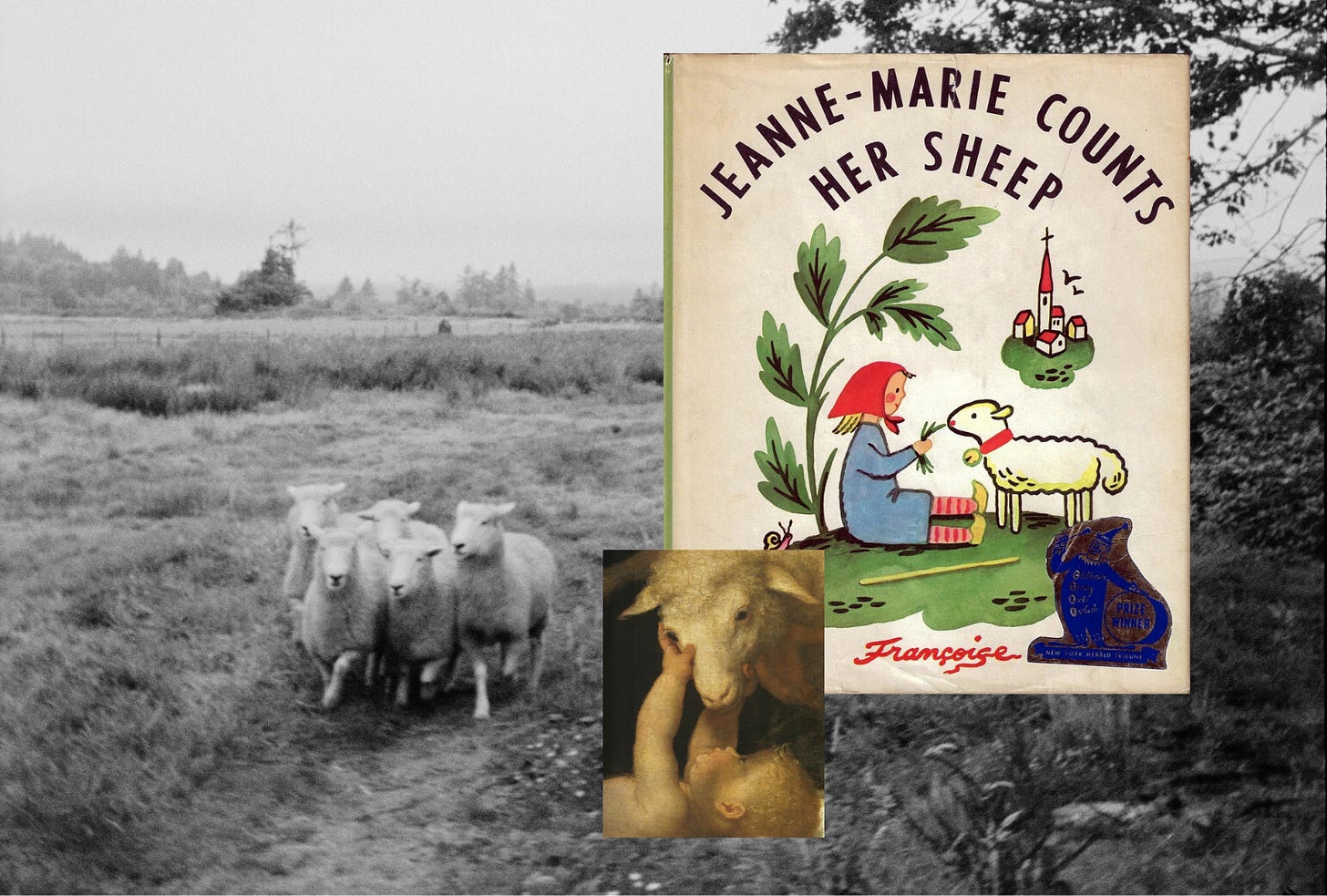

Immediately, Penny (pictured above at 10 months old) and Pierre start growing and learning how to be sheep. They transition from suckling milk to nibbling hay from the feeder and grass from the pasture. At six weeks old, Penny and Pierre receive a round of immunizations to keep them safe from tetanus and other bacteria. And at around three or four months, they are weaned from a diet of milk. Schiffgens separates the moms and mature ewes into one group, the lambs into another. For the first day, Penny and Pierre cry and call for their mom. It’s both cute and hard to hear; this is their first time apart and they miss each other. But Schiffgens and her children give the lambs a lot of attention during this time and soon, the lambs develop some independence.

At this age, they’re also ready for their first evaluation. One day, Schiffgens props Penny up onto a stand to make sure she’s healthy. She looks at how her legs sit on her hooves, measures how much meat she has on her loins, feels the curve of her spine, and closely examines her wool. Is it silky? Does she have a small curl, a medium curl, or a large curl? Is it light gray, medium gray, or dark gray?

Schiffgens takes careful notes that help her determine the lamb’s fate. If the lamb has beautiful wool and seems like a healthy candidate to eventually birth babies of her own, she stays on the farm. (Schiffgens’ main priority is breeding Gotland sheep to the Swedish standard, which requires a silky, three-dimensional curl with no cross fiber. I wrote about her breeding program via semen collection for LAINE Issue 25, which paid subscribers can read below, at least until I’m asked to take it down.) If the lamb isn’t going to improve the national Gotland herd (by its wool/pelt quality and overall conformation), it will be raised on grass to feed a family and provide a pelt. On Schiffgens’ farm, these lambs are loved like any other lamb, and only know one bad day: market day.

The reality is, like with all livestock, some animals end up as meat. Farmers, especially those who operate at a small scale, must make choices that are both economical and ethical. Another farmer I know in Oregon regularly provides lamb meat to an upscale restaurant located within

driving distance from their farm. What do you think farm-to-table means?

As for Penny? She gets to stay. Her heavenly lamb fleece—a once-in-a-lifetime wool that’s prized for softness and warmth—was shorn at the end of August 2025. Throughout her life, she will continue to produce shiny, curly wool that Schiffgens will either sell to fiber artists or keep for herself to craft.

Schiffgens tells me that she usually keeps ewes for three or four years before sending them to a new farm. That said, one of her ewes, Elsa, is 13 years old. No matter how long they stay, each of these animals is beloved. Wool is just a bonus.

Domesticating the mouflon

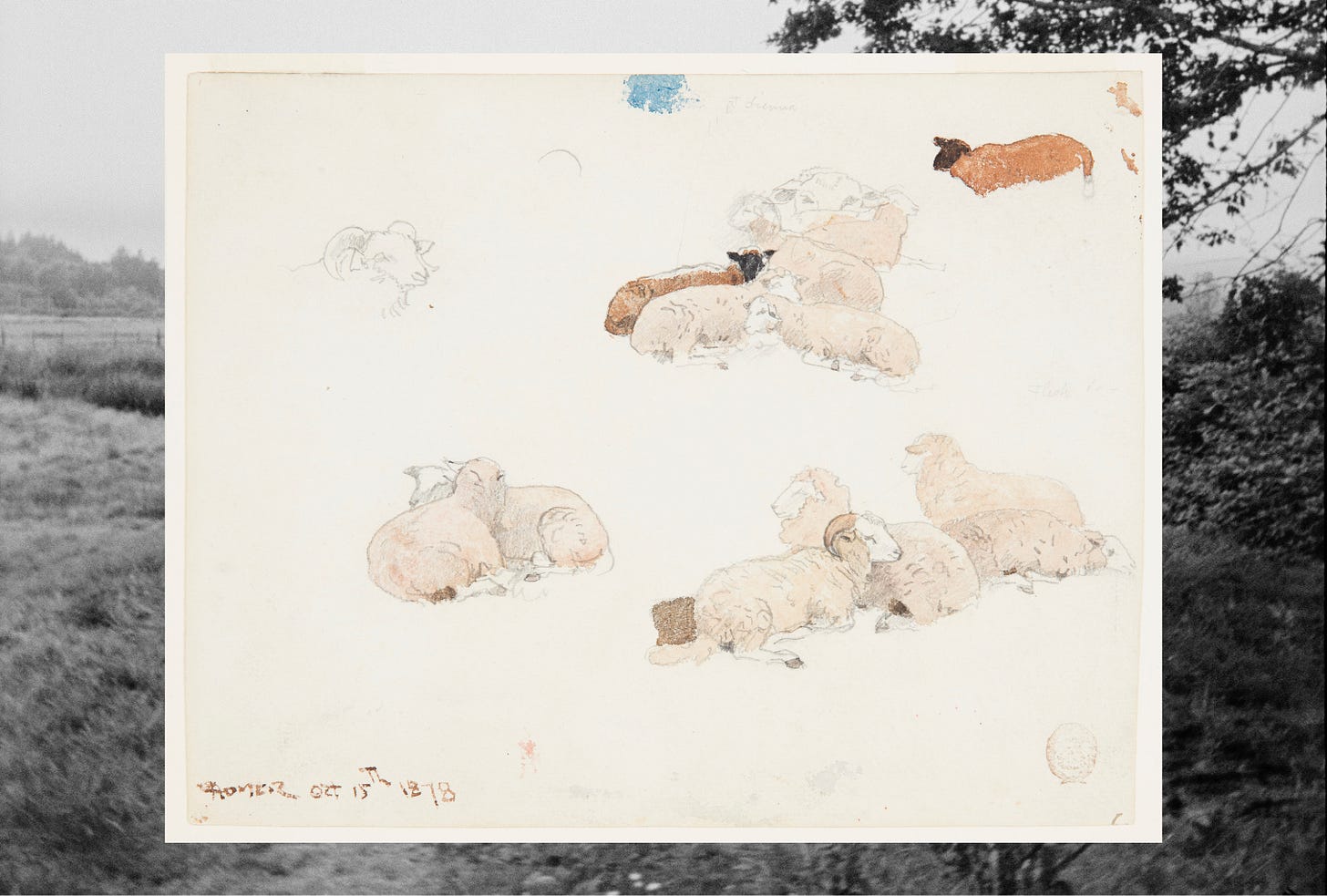

Sheep have not always been the fluffy animals—clouds of wool on legs, if you will—that we know them as today. Way, way back between 11,000 BC and 9000 BC, when humans began domesticating animals, sheep were more hairy and wiry than woolly, similar to deer, dogs, and even their Caprinae brethren, goats. Sheep would grow a coat in the winter to protect themselves from the bitter cold and shed it naturally come springtime, often by furiously scratching their bodies against trees and rocks—much like this bear wriggling against the base of a tree trunk. But over millennia, the composition and texture of their coats changed.

One of the earliest known sites for the domestication of sheep is present-day northeastern Iraq at a proto-Neolithic archeological site, Zawi Chemi Shanidar2 (ZAH-wee CHE-mee SHAN-ih-dar). In a cave and the surrounding mountains, archeologists have uncovered tools made of stone and bone for processing grains and nuts—early signs of farming in the Fertile Crescent. Among the discoveries are skeletons of Neanderthals, one even buried with flowers, as well as “high proportions of immature sheep.”3 Another site is the ancient Neolithic settlement Asikli Höyuk (ah-shik-luh Hoy-yook), located in present-day Turkey, where archeologists studied the ground and found urine deposits that suggest humans, goats, and sheep lived closely around 8450 BC.4

“In the first phase of the domestication of sheep, people moved from hunting animals in the wild to keeping them in pens for slaughter later on,” writes Sofi Thanhauser in Worn: A People’s History of Clothing5 (one of my absolute favorite books). She writes that the second phase took a couple thousand more years, when in 4000 BC, “people in Mesopotamia realized they could extract materials from their animals other than meat and hides.”

Once humans began using wool to make clothing, sheep were bred selectively for a longer and thicker wool. Over time, they lost their ability to shed naturally and became dependent on humans for shearing their heavy coats—which can sometimes weigh up to 30 pounds. Thus, our ancestors shaped the sheep of today, and as a sheep shearer once told me, now it’s our responsibility to take care of them.

From the hornless Cheviot to the celebrated Merino, there are as many as 1,000 sheep breeds worldwide6. Ranging vastly in size, shape, and color, they are classified by their primary purpose: meat, milk, or wool. Fat-tailed sheep, like the Awassi, have meaty rumps and are therefore raised for, well, meat. Two breeds in the U.S. raised for dairy include the East Friesian and the Lacaune. Sheep raised for their wool are further categorized by their fiber type: fine, medium, long, hair, or carpet wool. While the Longwool, Lincoln, and Romney produce long-stapled wool with a large fiber diameter, the Icelandic, Karakul, and Navajo Churro grow the coarsest wool of all that’s used to manufacture carpeting. The Merino, meanwhile, is basically famous for its fine wool used commonly and widely in apparel. I’d bet money you have something made of Merino wool in your closet.

These big, squishy guys (pictured above) account for more than half the world’s sheep population7. The breed was first established in the Iberian peninsula (modern day Spain and Portugal) near the beginning of the 12th century8. Until Napoleon invaded Spain and spread the word about the prized breed, it was a capital offense to export a single sheep9. Then in 1797, the descendants of the Royal Merino Flocks were sent from South Africa to Australia, then later to New Zealand, where farmers evolved an even finer fiber that is still coveted to this day10. Mairin Wilson, owner of the natural fiber clothing company Mairin, writes more about this fiber breed in her newsletter The Mindful Designer's Almanac: “Most of today’s Merino sheep in Australia are Peppin Merino- originating from one imported Rambouillet stud (a ram used for breeding) from France.”

Though their wool might be why they’ve lasted for so many centuries, sheep have always been more than the sum of their fibers, as you’ll read below.

The sheep, personified

Mary had a little lamb. Counting sheep to fall asleep. Baa, baa black sheep, have you any wool? As long as sheep have been central to human survival, long before wool became a global commodity, they have played a symbolic role. In stories and folklore we still tell today, some of which date back thousands of years, they show up not just as pastoral animals grazing on the farm but as metaphors for purity, vulnerability, gentleness, sacrifice, power, guidance, and communal belonging.

In yet another Neolithic site called Çatalhöyük (cha-tal-HOO-yook) from 8000 BC, the remains and depictions of sheep and rams appear in shrines11. In the Mesopotamian and Sumerian religion, kings were called shepherds of their people. In Ancient Egypt, sheep are associated with gods and ritual sacrifice. In Celtic lore, sheep are linked to fertility. In China, the character for sheep/goat (羊) is embedded in words for beauty, virtue, and goodness. In the Bible, Jesus is called the Good Shepherd and the Lamb of God, slaughtered for our sins. In ancient Greece, sheep appear in mythology, such as the story of the Golden Fleece about a winged ram named Chrysomallos12. In one telling, the ram was sent by a cloud nymph to rescue her children from being sacrificed to the gods and after the ram carried them to safety to the Black Sea, he sacrificed himself and was placed among the stars with Aries. His shining fleece led to the quest of Jason and the Argonauts. These stories about sheep, lambs, and rams go on and on.

You might even think of more stories because likely, early in life, whether you were sent off to Sunday School or sung nursery rhymes (or both or, honestly, neither), you learned that the lamb is synonymous with purity, passivity, meekness, and innocence. This is also true of cultures outside the U.S.

“There is no more enduring emblem of innocence than the lamb, the little creature that suckles on its knees, shyly hides behind its mother and follows the ewe in the music of gentle bleating and tinkling bells,” per the Book of Symbols13.

If you’ve ever seen a lamb gamboling, you know this is true. They are sweet little things with knobby knees and luxurious wool. They bleat for their mothers and play around in the grass, mimicking flock members as they learn how to be sheep.

It doesn’t take much time, only a few months, for the little lamb to grow up, as with Penny and Pierre from earlier. The Book of Symbols continues: “Because the mildness and purity of the lamb make it especially vulnerable to the predatory and destructive, nature does not let us stay in lamblike innocence for long.”

Once a male lamb matures into a ram, the animal adopts new meanings: masculinity, strength, heroism, even violence. Rams both domestic and wild literally butt heads to assert dominance. No wonder Egyptians depicted the god Khnum with the head of a ram. Even today, hunters mount ram heads in their cabins and collect curled ram horns as the ultimate show of manhood.

But to call someone a sheep is an insult. To be a black sheep is to be a rebel, an outcast. The word “sheeple” describes someone who lacks independent thought and absentmindedly follows the herd. “Woolgathering” also isn’t much of a compliment; it means to indulge in aimlessness and imagination. A “wolf in sheep’s clothing” is evil cloaked as harmlessness. To “pull the wool over one’s eyes” is to deceive them. Sheep have just as many negative connotations as positive.

In my research so far, what is abundantly clear is that humans are completely entangled with sheep and their wool—in the stories we tell, the clothing we wear, and even the language we use. Peggy Orenstein, in her memoir Unraveling, notes: “We refer to the unspooling of responses in texts (a word derived from the same root as ‘textile’), emails, social media, and web comments as ‘threads.’ … We hang by threads, we lose the thread, we pick up the thread, we have common threads, we thread through crowds, our reasoning is threadbare—and that is not even starting on metaphors involving sheep, wool, fabric, weaving, sewing, knitting.”

What other metaphors come to mind? Drop a comment with your favorite—or tell me something you learned, something you want to learn, or something I didn’t cover that I missed—and I’ll see you next month for Chapter 2.

https://textileexchange.org/other-animal-fibers/

https://ehrafarchaeology.yale.edu/traditions/m084/documents/010

https://ancientneareast.tripod.com/Zawi_Chemi_Shanidar.html

https://popular-archaeology.com/article/neolithic-site-reveals-transition-from-hunting-and-gathering-to-animal-herding/

https://craftcouncil.org/articles/wild-and-woolly/

https://www.sheep101.info/sheeptypes.html

https://www.sheepandgoat.com/merinosheep

https://breeds.okstate.edu/sheep/breeds-of-merino-sheep.html

https://www.sheepandgoat.com/merinosheep

https://www.woolmark.com/fibre/the-history-of-merino-wool/

https://www.persee.fr/doc/paleo_0153-9345_2006_num_32_1_5171

https://www.theoi.com/Ther/KriosKhrysomallos.html

https://archive.org/details/bookofsymbolsref0000unse/page/6/mode/2up

Bonus for paid subscribers: Read my LAINE Magazine article from summer 2025 about Stéphanie Schiffgens and her Gotland sheep breeding program. You can also join the subscriber chat, where I’ll send updates, book recs + topics to discuss.